Seasonal Affective Disorder: Everything to know about this cyclical condition

February 5, 2026Categories: Blog Posts

As the darkness creeps in by 5 p.m. and irksome snowstorms severely limit travel and socialization, it’s easy to feel a sense of the “winter blues” at the beginning of the year. But for some people, this season brings more than just a few days of tiredness or moodiness. In the U.S., approximately five percent of adults experience Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD)—a cyclical major depressive disorder that negatively impacts how they function daily.

As the darkness creeps in by 5 p.m. and irksome snowstorms severely limit travel and socialization, it’s easy to feel a sense of the “winter blues” at the beginning of the year. But for some people, this season brings more than just a few days of tiredness or moodiness. In the U.S., approximately five percent of adults experience Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD)—a cyclical major depressive disorder that negatively impacts how they function daily.

SAD, as its name suggests, has a seasonal pattern. While some people are affected in the warmer months, the majority have a cold weather cycle. According to Anna Zacharcenko, PsyD, a clinical health psychologist and the director of the behavioral health education residency program at St. Mary Family Medicine Bensalem, SAD can actually begin in the fall, as the days start to get shorter.

“You will see symptoms of depression, such as diminished interest or pleasure in activities; isolation and social withdrawal; feelings of sadness; irritability; overeating—especially in the winter pattern—and craving carbs, which can lead to weight gain; and hypersomnia, which is sleeping excessively. As the person is withdrawing, it’s almost like they’re hibernating like a bear,” says Dr. Zacharcenko.

Those at high risk for experiencing SAD include individuals who: live a good distance away from the equator where there’s less sunlight and harsher winters; have a family history of depression; have a personal history of mental health problems; are women. SAD can begin anytime in adulthood, starting around 18 years old.

More than the ‘winter blues’

To differentiate between SAD and the “winter blues,” explains Dr. Zacharcenko, a person must demonstrate at least two episodes of this depressive disturbance over the previous two consecutive years. Additionally, seasonal episodes of depression should substantially outnumber non-seasonal episodes—if they have the cold weather pattern, symptoms are essentially nonexistent by the spring.

“There also has to be evidence of significant functional impairment. The person is not able to fulfill their daily duties and the symptoms are interfering with life. They’re so depressed, they’re incapable of fulfilling their occupational or academic responsibilities. They may withdraw so much, they can’t be there emotionally for their children, spouse or loved ones,” says Dr. Zacharcenko. “Maybe there’s a week where we might feel blue after the holidays, but we recover from it. This is not recovering in a couple of days.”

Sleep disturbance is a major part of SAD—either sleeping too much or not getting good quality sleep—which can greatly amplify the other symptoms. According to Dr. Zacharcenko, the circadian rhythm becomes disrupted with winter’s reduced sunlight, throwing off the production of serotonin (which improves our mood) and melatonin (which balances our sleep/wake cycle).

“For a lot of mental health disorders, we target sleep disturbance first. When sleep gets out of its good, productive pattern where a person feels well-rested, that’s going to cause all kinds of problems,” says Dr. Zacharcenko. “We might see it in anxiety, psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder.”

Treatment options

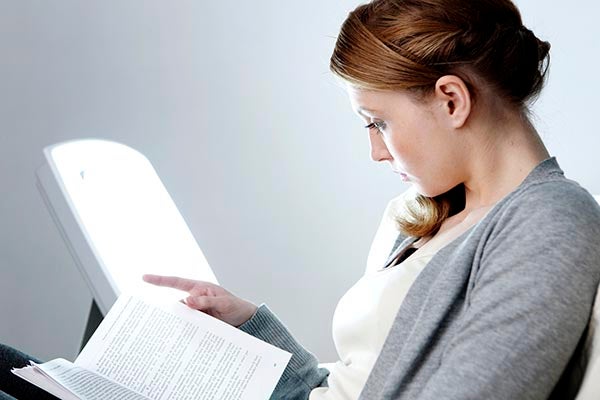

Light therapy and vitamin D are often used to help SAD patients reset their circadian rhythm and lessen their symptoms, in addition to talk therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Regarding CBT, an important component is behavioral activation, which helps those experiencing SAD not withdraw from the activities that normally bring them pleasure.

“We want them to have a structured schedule where they still keep doing things. Some people stop going to the gym, they’re not bike riding because it’s too cold outside. We don’t want them to totally eliminate exercise if it is a form of improving their mood,” says Dr. Zacharcenko.

She urges those with SAD to have discussions with a behavioral health therapist or primary care provider to ensure that, prior to their SAD cycle beginning, they have an engaging activity schedule/plan of action—one they’ll stick to once those days become shorter. This plan may include regular light and/or vitamin D therapy; stepping outside for a certain number of minutes daily; tracking sleep; not overextending themself, especially around the holidays; and not putting physical activity to the side, even if it’s a quick YouTube workout in the living room.

Final words

SAD can be difficult to navigate for not only those experiencing it, but also their loved ones, who may feel helpless as they watch their parent/sibling/friend withdraw for months at a time. For those in this latter group, Dr. Zacharcenko shares how to approach the topic: softly and with love. They should keep track of what they’re seeing over time and gently express their concern.

For anyone who thinks they may be at risk for or have Seasonal Affective Disorder, Dr. Zacharcenko says, “Pay attention. Be mindful of your energy levels. Watch what you’re doing and how you’re behaving, how you’re sleeping. Think about whether you’ve seen this pattern before. Be honest with yourself about it. And if you have seen this pattern before and you’re concerned about it, pick a person to share it with, whether it’s a primary care physician or a loved one.”